Beyond Gun Violence Prevention: Student Safety in Today’s Schools

Stephen Brock, a school psychologist, knows that by almost every measure, the nation’s schools are the safest they’ve been in years. He also knows the demand for increased protection is justified.

“When we send our kiddos to school, we expect them to be safe. And we have every right to believe that that’ll happen,” Brock said. “One act of school violence, one act of school aggression, one [act of] school-associated violence — that is one too many.”

Since the February shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla., schools, students and policymakers around the country have discussed or implemented almost every security measure imaginable: armed teachers, clear backpacks, miniature baseball bats — even buckets of rocks in classroom closets.

But the school safety puzzle also includes threats like bullying and gang violence, forcing schools to strike a balance between preventing violent outcomes and promoting welcoming environments.

How Safe Are Our Schools?

In the past 20 years, certain safety measures have gone from rare to standard in schools. Today, more than 80 percent of public schools use security cameras, compared to less than 20 percent in 1999, according to U.S. Department of Education data. During that same period, an additional 40 percent of schools added a requirement for staff to wear badges or picture IDs, and the number of schools with controlled access to their buildings increased from 74 percent to 94 percent.

Paul Timm, vice president of Facility Engineering Associates and a school security consultant, says physical security typically falls into four categories: deterrence, detection, delay and response.

- Deterrence aims to discourage criminal activity from ever happening. Examples include good exterior lighting, trimmed vegetation to reduce cover for criminals, and “No Trespassing” signs.

- Detection asks, “How can we find threats before they happen?” Examples range from video surveillance and communications systems to access control and visitor management.

- Delay is about slowing the threat. The simplest, and potentially effective, example is classroom doors that lock from the inside.

- Response ensures an efficient reaction to threats. What resources are immediately available when someone responds? Examples include first-aid kits and defibrillators.

Schools are doing more than installing new technology to prevent violence. Ron Avi Astor, a professor at USC Rossier, says the focus on how to approach school safety is changing — the context of violence matters.

“It’s not a generic juvenile delinquency question or a childhood aggression question,” he said. “The question is, What happens in those spaces that makes those spaces more vulnerable?”

“…strong social relationships between students, between teachers and students, between parents and teachers, between principals and students, is probably the best way to have a safe environment.”

— Ron Avi Astor, USC Rossier professor

With that change comes an increased emphasis on psychological security — things like relationship-building, discipline strategy and suicide risk assessment. According to Brock, a member of the National Association of School Psychologists’ School Safety and Crisis Response Committee, schools need to place as much emphasis on psychological safety measures as they do on physical ones.

One example Brock points to is the “conspiracy of silence” — when a student hints at violent behavior, whether toward themselves or others, and their peers say nothing. “By facilitating school environments where students feel adults care about them … they’re more likely to tell,” he said.

Astor said the evidence to support strengthening psychological security is overwhelming, with decades of studies showing “strong social relationships between students, between teachers and students, between parents and teachers, between principals and students, is probably the best way to have a safe environment.”

Overall, threats at school are on the decline, according to the U.S. Department of Education. The number of students involved in physical fights has dropped 50 percent since 1993, and the number of students who have brought weapons to school declined 66 percent. Gang presence in schools has also decreased, and fewer students experience bullying than 20 years ago.

Violent crime is rare in schools, but it still happens. How can schools evaluate the intent of security measures before moving forward? Should resources be used to prevent the most extreme, but statistically rare, scenarios? Or should school climate and psychological safety be the focus?

How Safe Are Our Students?

Security cameras, visitor protocol and communications systems can all be useful in keeping schools safe, but they are most effective when used as part of a broader strategy. Balancing physical safety measures with “softer” psychological approaches to create a reality of safety and a feeling of safety are key, experts say. When students feel safe, the effects are widespread.

“This is more than just a school safety issue,” Brock said. “This is, in a very real sense, an academic issue.”

Research shows that students who feel safe are more engaged in classes and less likely to report symptoms of depression and aggression. So, do more security measures make students feel safer? Sometimes. According to Mo Canady, executive director of the National Association of School Resource Officers, visibility matters.

Today, more than 80 percent of public schools use security cameras, compared to less than 20 percent in 1999.

— U.S. Department of Education data

“As a police officer for 25 years, I know that my presence helped to deter crime,” he said.

But Astor said law enforcement presence isn’t always suited for schools.

“Having a police officer just outside my door doesn’t necessarily mean I’m going to learn math better,” he said. “I may feel more anxious.”

According to Brock, students feel safer when there isn’t a mismatch between what the real threats are to a school, and the response. For example, in a community surrounded by gun violence, metal detectors may make students feel safer. Conversely, installing metal detectors in a school where there isn’t a need could “reduce your perception of safety and security, because now you perceive the environment as more dangerous,” Brock said.

School Climate Questions for Educators

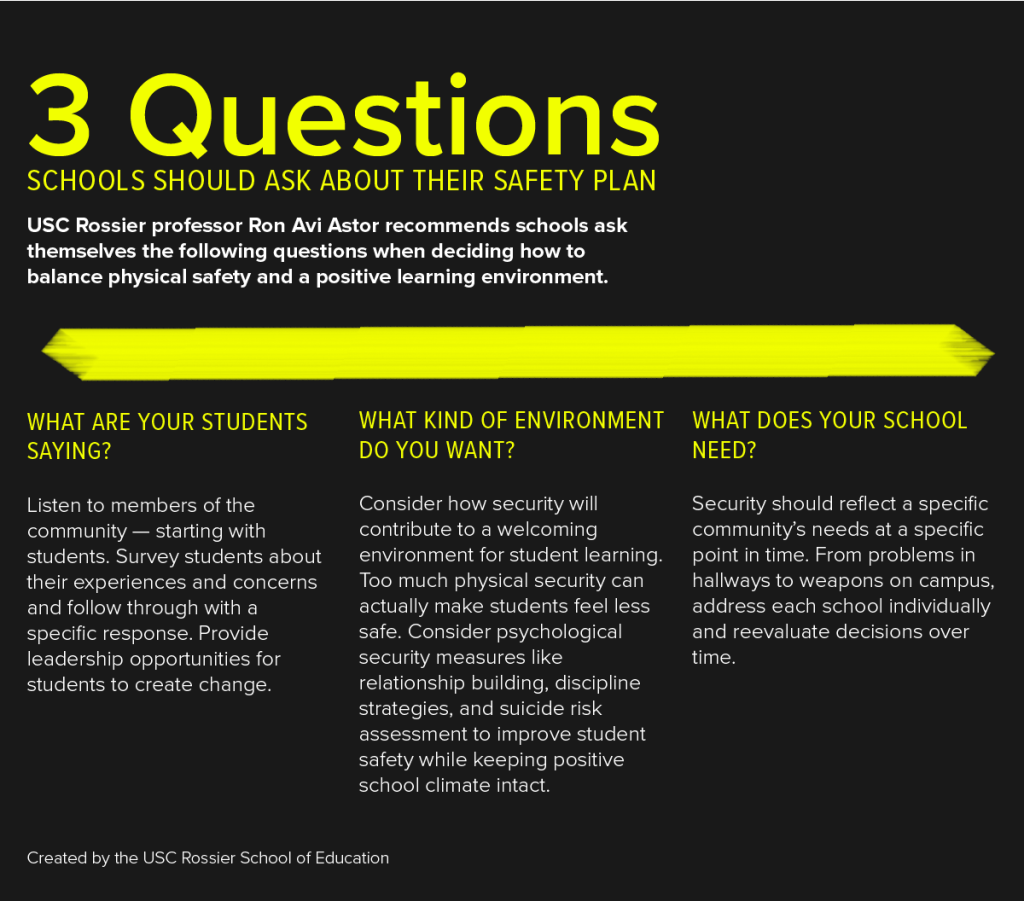

Every school has the opportunity to use both physical and psychological security measures to achieve the highest level of student safety. Before selecting and funding new systems, schools should try and answer the following questions to find the best balance.

What are your students saying?

Listen to members of the community — starting with students. Survey students about their experiences and concerns and follow through with a specific response. Provide leadership opportunities for students to create change.

Finding out what is needed begins with listening to the people in the community. Experts agree students should be included in the conversation about how to keep their school safe. The walkouts, marches and legislation sparked by Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School students are proof they are up to the task.

Astor said there are high schools all over the country with student leaders, and providing meaningful ways for them to get involved signals their schools are behind them.

“We see [students] as a group to service from top down,” he said. “And I think we would do better from a safety perspective if we unleashed some of their power.”

Brock agrees high school students are more than capable of being a part of the conversation, but he worries about placing blame with the power. He cautioned against allowing the leadership of students to let adults off the hook for their role in school safety.

“We need them. We want to include them,” he said. “But ultimately school safety is the responsibility of the adults that are part of the system.”

What does your school need and when do they need it?

Security should reflect a specific community’s needs at a specific point in time. From problems in hallways to weapons on campus — address each school individually and reevaluate decisions over time.

Every school can benefit from a specific, timely evaluation of the threats posed to their community and students. Astor said asking students what they’re experiencing on campus is important, but that information needs to guide the decisions that follow.

“You have to do it on a school-by-school basis,” he said. “The school has to go through a process through which they choose that they want to work on certain things and they see it as a priority to do it.”

Schools should use the data gathered from students about threats on campus to guide safety decisions. But in order for security to last, it also needs to fit into the school hierarchy, Astor said. He compared safety policies to a school’s air conditioning system — the more centrally located, the better impact they will have. Anything focused on the outside of that system, the “window air conditioning,” won’t have as much influence on students.

“The kids learn that quickly, teachers learn that quickly — that the centrality of the information and who uses it as an intervention is really important,” he said.

Districts should first ensure their school counseling departments are well-staffed and funded. School counselors are trained experts in improving the school climate that Astor noted is so important to keeping students safe. They’re part of the “central air” system that helps make policy effective.

Canady, a former school resource officer, said SROs should not take the place of teachers and trained counselors. But when they’re specifically selected and well-trained, SROs are “different from just an armed guard,” he said, “It’s an officer engaged in community-based policing in the school and really with enough opportunity to make a huge difference.”

What kind of environment do you want?

Consider how security will contribute to a welcoming environment for student learning. Psychological safety measures like relationship-building, discipline strategy, and suicide risk assessment can contribute to student safety while keeping that positive school climate intact.

Ignoring psychological safety changes the environment students spend so much time in.

“Once you go the route of the hardening, you create a generation of kids who basically grew up in prisons,” Astor said. “We don’t know if that’s good for learning.”

Schools need to reevaluate how their climate contributes to the major function of education, he said, “not because we want schools just to get kids into college, but because we want a better society.”

Resources for Schools

USC Rossier created a summary graphic of these tips for educators and parents to share online. Please feel free to embed the following on your website.

A lengthened PDF version is also available for download. This is meant to provide a printable, complete resource for administrators and teachers to use in classrooms. Please feel free to share with your network and school community.

Citation for this content: USC Rossier’s online master’s in school counseling program.